JMP Blog

A blog for anyone curious about data visualization, design of experiments, statistics, predictive modeling, and more- JMP User Community

- :

- Blogs

- :

- JMP Blog

- :

- The art of what’s possible in semiconductor: Making the best choice for defect ...

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

In semiconductor manufacturing, defects can result in scrap and sunk costs. When not detected, they can adversely impact device functionality and cause end-user failures. Defects can lead to large financial losses and damaged reputations. There is value in making the statistical models used to minimize defects as accurate as possible. Standard least squares regression is often the go-to method for building the statistical models of semiconductor processes used to solve defect problems. But should it be? Quality measures like defect counts, that are used as response variables, often violate assumptions that must be met for standard least squares regression models to be successful. What should be used instead?

Counting defects on a die (chip) or wafers is a standard quality requirement in semiconductor manufacturing. For example, counting abnormalities like corrosion and scratches in a chemical mechanical planarization process (CMP) is quite common.

A defect count quality metric differs from a continuous quality metric, like film thickness, used for a chemical vapor deposition process (CVD) both physically and practically. Defects are counted and reported as integer values from zero on up. For many types of defects, we expect most observations to be zero or near zero like the skewed right distribution graph on the left below. Different defect count levels may also associate with different failure mechanisms. Conversely, we expect continuous measurements to be reasonably symmetric on either side of a target, like that of the normal distribution graph on the right. The shape and scale of a continuous metric is typically a result of only one physical phenomena. For a “center is best” type of process variable, the distribution on the right would be indicative of a process that is stable and running on target.

|

|

To be effective, a statistical model of a defect count response must be able to describe or predict process scenarios that may generate zero to many counted defects. A statistical model with a continuous response must be able to describe or predict process scenarios that lead to variations around a process target. Given the differences in the physical and practical aspects of these process quality metrics and their model expectations, shouldn’t the methods used to generate the models be different? It turns out that using a standard least squares regression approach may lead to inaccuracies for defect count responses.

|

|

|

CMP Process Diagram |

CMP Scratch Defects |

|

Source: Scratch formation and its mechanism in chemical mechanical planarization (CMP), Friction, Kwon et. al., 2013. |

|

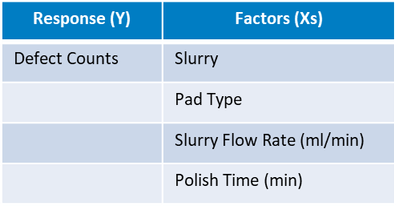

Consider a scenario where a process engineer is tasked with reducing the number of scratch defects coming from a CMP tool. To begin, they gather a month’s worth of observational process data with the intention of generating a statistical model to help understand what process variables may be leading to scratch defects. Drawing from experience, they include slurry type, polishing pad type, slurry flow rate, and polish time factor data.

Our process engineer uses the Fit Model Standard Least Squares personality in JMP for a first attempt at a model. Then using the prediction profiler, a combination of factor settings that minimize defects is determined, only to discover the model outcome is a negative average defect count.

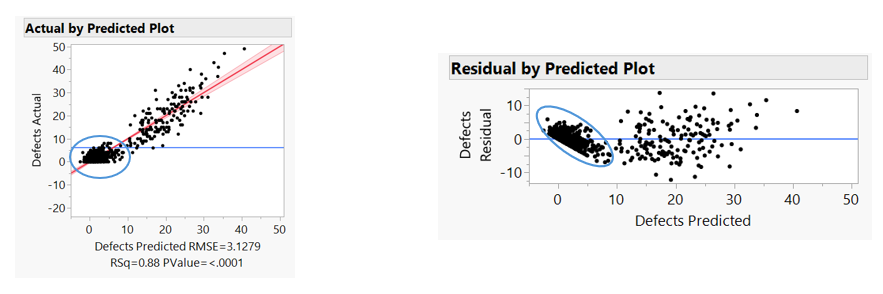

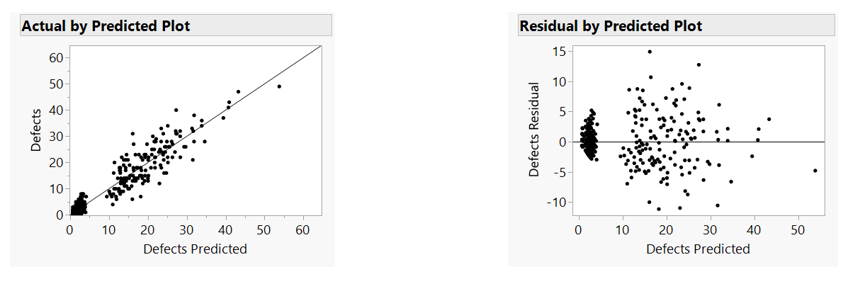

Even though standard least squares is mathematically possible for the CMP example, a negative defect estimate is clearly not realistic. We can get an idea of why there is an issue with the method by looking at the actual by predicted and the residual by predicted plots.

In both plots, a pattern exists for lower defect counts. The pattern shows that the model is not performing well for lower defect counts. We expect to see random scatter on either side of the diagonal in the actual by predicted plot and a random scatter of residuals about zero in the residual by predicted plot – as we would for higher defect counts. This is likely due to the that fact that most of our observations are zero or near zero. Model accuracy at predicting zero defects is important for optimization. Model accuracy at low defect counts is important to our process engineer, as even one or two defects can kill a die. There is also nothing in the model that limits defect count estimates to zero and greater. Standard least squares regression is built upon regression to the mean and given distributions such as defect counts, the mean is often not a good measure of central value.

Standard least squares regression is simply not the best approach to model the CMP process with respect to these defects. So, what is? Is there a type of regression analysis that can help deal with non-normal and skewed defect distributions? The answer is most definitely yes.

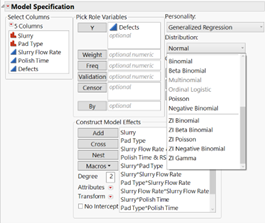

For the CMP scenario, our process engineer learns about the distribution options available in the Generalized Regression Fit Model personality in JMP Pro. Generalized regression is a multipurpose linear modeling tool. There are not only a variety of distribution options but also variable selection techniques and options for dealing with censored data, making it useful in many modeling situations where standard least squares may fall short. Our process engineer learns that the Poisson and negative binomial distributions are often effective for modeling defect count type data. They also learn that zero inflated versions of these distributions, e.g., ZI Poisson, may work better in circumstances where there are many zero-defect observations.

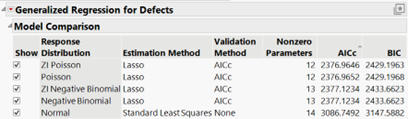

To get a baseline for reference, our process engineer starts with a normal distribution, then attempts fits with Poisson, ZI Poisson, negative binomial and ZI negative binomial distributions using a lasso estimation method.

Judging by the Akaike Information Criterion adjusted for small sample size (AICc), all models except the normal response standard least squares model are performing similarly. The AICc statistic is often used to compare the relative quality of models that are fit using different methods. As a general rule-of-thumb, if the difference in AICc between two models is 2 or more, then it can be said that the model with the smaller AICc is strongly preferred[1]. The lasso estimation method has reduced the number of model parameters compared to standard least squares. Given similar AICc statistics, the model with the fewest parameters is often judged to be better. Even more important to model selection is an understanding of which model matches the characteristics of the process generating the data or some historic precedence. Our process engineer knows that scratch defects do not occur often for the CMP tool under study, so zero inflation is expected. Our process engineer is now able to confidently select the ZI Poisson lasso model based on AICc, number of parameters, and process understanding.

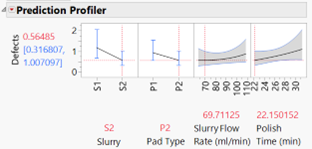

Results for the new ZI Poisson model with shrinkage look much more realistic. The model is not estimating negative average defects.

There is also less of a pattern in the actual by predicted and residual by predicted plots for lower defect counts. The points are more evenly balanced on either side of the diagonal in the actual by predicted plot and more even above and blow zero in the residual plot.

With a reasonable model in hand, our process engineer is one step closer to solving their CMP process defect problem.

In summary, standard least squares regression has limitations. Applying the method broadly to every analysis situation may lead to inaccuracies, as was the case with the CMP example. A better approach is to use flexible modeling tools that can be adapted to the characteristics of the data like the Generalized Regression platform in JMP Pro that surfaced an effective model for the CMP process data. The Generalized Regression platform will also generate a least squares model for a normal response distribution and non-censored data, making it available for comparisons and to be used if it is best for the situation at hand.

For more information on generalized regression, refer to Clay Barker’s developer tutorials, Using Generalized Regression to Analyze Observation Data and Using Generalized Regression to Analyze Designed Experiments.

[1] Russell B. Millar, Maximum Likelihood Estimation and Inference (Wiley, 2011)

- © 2026 JMP Statistical Discovery LLC. All Rights Reserved.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Contact Us

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.