I hope to help you avoid some mistakes in data analysis.I’ve been a practicing engineer for many years now. Along the way, I’ve seen many tests performed, and many different ways to analyze data. More often that I care to admit, I’ve been on teams that have made one or more mistakes on the job. The end result was a cost to the company in time and money.

I hope to help you avoid some mistakes in data analysis.I’ve been a practicing engineer for many years now. Along the way, I’ve seen many tests performed, and many different ways to analyze data. More often that I care to admit, I’ve been on teams that have made one or more mistakes on the job. The end result was a cost to the company in time and money.

I thought some readers might like to learn from my mistakes, so I came up with a fictitious scenario that embodies the various problems I’ve come across in my work.

Although my scenario is a mechanical engineering example, it is both simple and generic enough that you should find it easy to translate to your particular discipline. We will explore this scenario in this and upcoming blog posts.

The Scenario

We are trying to improve the strength of a product. We have identified a treatment “A” that we believe will improve strength. Our management wants us to prove it before implementing the change in production.

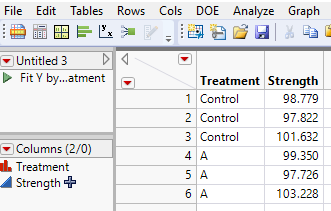

We create three samples with Treatment A and measure the strength of each. We also collect three standard (or Control) samples and measure the strength of each. Here is the data:

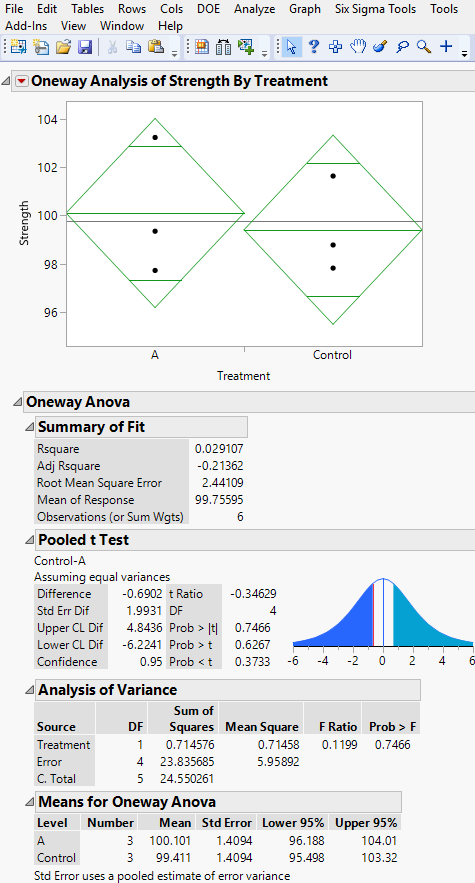

Using the Fit Y by X platform in JMP (see below), we find that the average strength from the Treatment A sample is slightly higher than the Control. However, the t-test says that we cannot say (at 95% confidence) that the population mean of Treatment A will be any different than the population mean of the Control. We stop the test and start looking for another way to improve product strength.

This seems like a simple test with simple-to-interpret results, but I contend that mistakes are being made in the above scenario, and that we might be throwing away a perfectly good solution.

What do you think they might be? Stay tuned for my next post in this series, coming in about a week!