So this is me: I am a fairly healthy 36-year-old male living in Austin, Texas, USA. While somewhat active throughout my teens and twenties, post-marriage and kids has seen me become a bit too sedentary, a bit too lazy, and much too easily winded. In May 2019, my wife and I took our kids for a hike, with me bringing our youngest (at the time) in a backpack carrier. After 2+ miles of fairly level terrain, I was exhausted. This precipitated a sea change in my activity.

On 27 May 2019, I started running. It was terrible. I hated it, yet I loved it. Three months later, I was talked into running a 10K trail race (at night), and I was hooked! Four months later, I heroically and quite stupidly ran a 50K trail race. It took me over an hour longer than I’d anticipated. I couldn’t walk for a week, and when I crossed the finish line, it took every ounce of self-control to not openly weep.

Kilometer 27-ish of the Bandera 50K. I completely tanked about 2 kilometers later but still managed to (barely) finish the race.

Kilometer 27-ish of the Bandera 50K. I completely tanked about 2 kilometers later but still managed to (barely) finish the race.

Fast-forward to today: I am ramping up for a series of four races longer than 60K over the next 10 months. Time to train is at a premium. So as I am running, I am continually asking myself this question: What is the most efficient way to improve my running economy in a minimum amount of time? Enter design of experiments (DOE).

DOE is a mechanism to most efficiently use selected input variables to draw conclusions about pre-determined output variables. If it’s good enough to design top-of-the-line semi-conductor components, it ought to be good enough to help me run faster without running longer. So, what is my plan?

Well, there are some variables that I cannot control but I know are important: weather, mileage (I am using a prescribed training plan), hours of sleep, my weight, etc. These parameters are being tracked, just not controlled. But there are parameters I can control:

- Warm up — a 5-minute warmup on a rowing machine (I never warm up.)

- Caffeine — drinking coffee right before my run (I prefer my coffee after I run.)

- Timing of run — first thing in the morning or afternoon (I love morning runs.)

- Shoes — trail or road shoes (Usually it's road shoes on the road and trail shoes on the trail.)

- Diet — Did I eat meat in the previous 24 hours? (I’m very curious to see if this has an effect.)

- Running hydration — water or electrolyte (I prefer water.)

- Apparel — 7”, 5”, or 2” inseam shorts*

*A fellow JMP Systems Engineer (and endurance runner) and I have a pet theory that shorter shorts make you run faster. It’s time to test this theory once and for all.

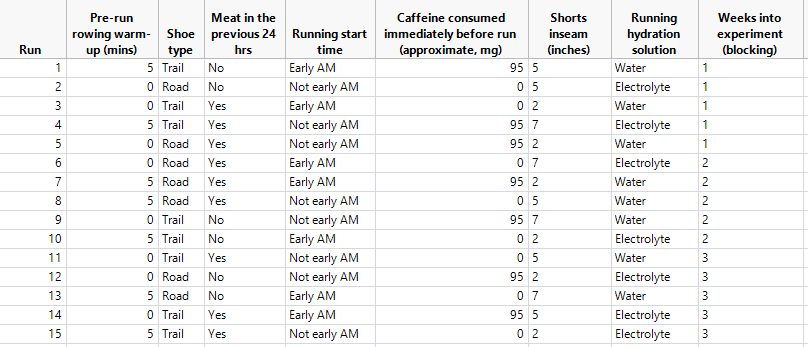

I will be completing five runs a week for three weeks (see the table below). Through all my runs, I will try to maintain a Zone 2 heart rate to ensure the effort I put into each run is quantitatively consistent. For me, this means I will try to maintain a heart rate between 139 and 144 beats per minute (bpm), while trying to stay as close to 144 bpm as possible. I will also temporarily sacrifice my love of trail running and keep all my runs on roads/sidewalks to maintain consistency.

The JMP-generated DOE trials

The JMP-generated DOE trials

So how will I track progress? In addition to recording variables I cannot control, I will specifically track these three parameters:

- Grade adjusted pace (GAP) — pace in minutes per mile normalized for topography

- Average heart rate — while trying to maintain an average heart rate of 144 bpm, variability is sure to occur

- Perceived exertion — a subjective 1-10 measure of how I felt immediately after the run

An improvement in these three outputs is how I am gauging an improvement in efficiency — can I run faster, with a lower heart rate, and upon completing a run, do I feel like I exerted less energy.

Now, if I complete 15 runs over three weeks I will hopefully improve my running efficiency even without controlling these inputs, just by the sheer fact that I am running regularly. To account for this, my design uses week as a blocking variable. As a result, when I build the model upon completing this experiment, JMP will account for week-dependent impacts in running efficiency and subtract them out of the model. This will allow me to better estimate the impact of the factors am trying to study.

If you will excuse me, it’s time to hit the road!