- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark Topic as New

- Mark Topic as Read

- Float this Topic for Current User

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Printer Friendly Page

Discussions

Solve problems, and share tips and tricks with other JMP users.- JMP User Community

- :

- Discussions

- :

- Re: Interpretation about Split Plot Design Example in JMP

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Get Direct Link

- Report Inappropriate Content

Interpretation about Split Plot Design Example in JMP

Hello, I have a question about the example of Split Plot Design Example, introduced in JMP webpage.

https://www.jmp.com/support/help/14-2/split-plot-design-example.shtml

In this explanation, an animal identification code called subject, with nominal values 1, 2, and 3 for both foxes and coyotes. Then it was nested in species. Then subject[species] was selected as random effect, and then REML methos was selected.

My questions

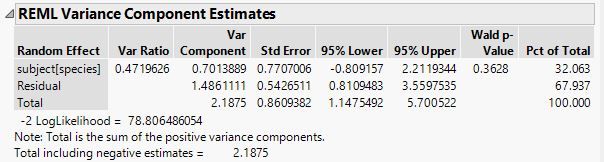

1) In the below table,

subject[species] has 0.7013889 variance component. How can I interpret this? Does it mean the 70% error is coming from 'subject[species]' ?

For fixed effect test, species and season are significant respectively.

2) If I use simple two way ANOVA (species x season), in this case "subject" was considered as "block"

In this case, main effect was significant, whereas its interaction was not significant, and also block (subject-animal identification code) was also significant.

Even though I use ANOVA or Split Plot Design (or REML), the result is the same, why do we need to use Split Plot Design (or REML)? For what purpose?

Could you tell me why?

Many thanks,

Sincerely,

JK

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Get Direct Link

- Report Inappropriate Content

Re: Interpretation about Split Plot Design Example in JMP

- Mark as New

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Mute

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Get Direct Link

- Report Inappropriate Content

Re: Interpretation about Split Plot Design Example in JMP

1. No, it is not a proportion (relative) but the actual variance estimated by REML. Take the square root and you have the estimated standard deviation between subjects.

2. It is generally better to identify (and estimate) the between and within error when possible. The split-plot analysis is an example of such a model. You have two sources of variability that might be sampled at different rates. (This matter is about randomization and levels of experimental units.) If you include only one error term, then the estimate is some kind of average that can inflate the type I error of the hard to change factor and inflate the type II error of the easy to change factor.

It isn't a matter of trying different ways but understanding how the model terms and assumptions match the design and the way in which the data were collected.

Recommended Articles

- © 2026 JMP Statistical Discovery LLC. All Rights Reserved.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Contact Us