- JMP User Community

- :

- Blogs

- :

- JMP Blog

- :

- The importance of risk literacy

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

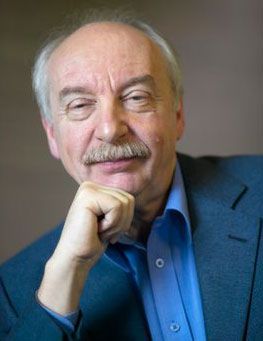

Gerd Gigerenzer, Director of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, and author of Calculated Risks, Gut Feelings: The Intelligence of the Unconscious, and Risk Savvy: How to make good decisions, explores these questions in his keynote talk at Discovery Summit Europe, 14-15 March in Frankfurt.

Gigerenzer calls risk literacy “the cement of society” and argues that even the experts themselves often lack it.

“Many judges, doctors, journalists and politicians alike do not understand statistical evidence and can be fooled into wrong conclusions without noticing," he says.

I asked him a couple of questions to preview his talk, Risk Literacy: The Cement of Society.

You say that the general public lacks risk literacy, and sometimes experts do, too. What are some steps we can take personally to improve our risk literacy?

Start with Benjamin Franklin’s piece of wisdom “In this world there is nothing certain but death and taxes.” This holds in the digital age as well – it would be an illusion to believe that Big Data, innovative financial products, or artificial intelligence provide certainty. Next, make an effort to improve your statistical thinking – a good way is to learn the major tricks that medical and financial institutions use to mislead customers (unstatistik.de). Finally, consider Immanuel Kant’s motto for the Enlightenment, “Sapere aude!” That is, have the courage to know.

You mention that sometimes people need “nudges” to steer our behavior toward what is best for us. Can you give us an example of how this works?

The philosophy of nudging assumes that people lack rationality and that there is little hope of remedying this. In its view, the government, therefore, needs to step in and steer people like sheep. That is not my vision of the 21st century! Instead of governmental paternalism, we should work on educating people to become risk literate.

Here is an example. Consider the appointment letters sent in many countries to women above age 50 for mammography screening. These letters contain a fixed time and location. This default booking is a nudge that exploits inertia — those receiving the letter might not make the effort to actively sign up or, similarly, to decline the appointment. Furthermore, in the letters and pamphlets encouraging screening, it is often stated that early detection reduces breast cancer mortality by 20 percent.

That figure is a second nudge that takes advantage of those with limited understanding of statistics. As it stands, screening reduces the number of women who die from breast cancer from about 5 to 4 in 1,000 (after 10 years), which in absolute numbers amounts to a risk reduction of 1 in every 1,000. But to look more impressive, this figure is typically presented as a relative risk reduction of 20 percent, often rounded up to 30 percent. Many people automatically assume this to mean that 20 to 30 lives are saved out of 100, which translates into 200 to 300 per 1,000.

Here, nudging exploits people’s inertia and lack of risk literacy to steer them into screening, which is a lucrative business. The alternative that I prefer is to provide people with honest and transparent information about benefits and harms of screening or other medical therapies, so that everyone can make informed decisions themselves. This is the difference between nudging and education. We need competent citizens, not more paternalism.

Want to join us in Frankfurt to hear this speech by Professor Gerd Gigerenzer? It's not too late to sign up.

- © 2024 JMP Statistical Discovery LLC. All Rights Reserved.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- About JMP

- JMP Software

- JMP User Community

- Contact

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.